1. Background

One in almost every five people residing in the United States is of Hispanic origin. For decades, Hispanics have been one of the fastest growing populations in the nation, and from 2010 to 2020, this population grew from 50 million to 62 million people.1 In the Midwest, in certain states like Nebraska, it is estimated that by 2060, Hispanics will represent 24% of the total population of the state.2

COVID-19 is responsible for over 6 million hospitalizations and 1 million deaths in the United States.3 Nationally, marked racial and ethnic disparities in the prevalence and mortality of COVID-19 continue to exist, with Hispanic communities among the most negatively impacted.4 In the Midwest, these rates are also significantly underscored and sustained, partly because of the high density of essential industries established in the area. For example, in Douglas County, Nebraska, where the U.S. meatpacking industry is highly concentrated, Hispanics represent 13.4% of the population. However, during the peak of critical times when hospitalizations were high, and community cases were out of control, such as in the summers of 2020 and 2021, Hispanics in Douglas County represented 33% and over 50% of the COVID cases, respectively.5,6

These disparities are the product of structural and historical challenges in the U.S. health care system, such as discrimination, language barriers, health insurance coverage, and income, which also negatively impact the level of trust between patients and health care services.7 Furthermore, some of the most remarkable contributors to these disparities since the early phases of the pandemic were receiving timely health information for disease prevention in a language the community understands and the sophistication of the navigation of the health care services, such as having to make clinical appointments via mobile applications or webpage.8

A substantial body of the literature demonstrates that access to health information can improve health outcomes by increasing health knowledge, enabling people to make better-informed choices and adopt healthier behaviors.9,10 However, there is limited data on how Spanish-speaking Hispanics access health information, especially in the Midwest. For example, before the COVID-19 pandemic, D. Britigan and colleagues studied sources of health information used by Hispanics in the Midwest (Southwest Ohio). The major source of information for their participants was medical settings, and one of the less preferred sources was the internet.11 M. Kelly and colleagues conducted a similar study using a telephone survey across Douglas County, Nebraska. Hispanics made up 11% of the participants. Their results are consistent with D. Britigan’s study, where the primary source of health information was the medical settings, and the internet was less popular.12 Lastly, another study that examined Spanish-speaking Hispanics residing in rural and urban Nebraska also identified clinical settings as the major source of health information and websites and social media as less likely to be used for sources of health information.13

While some studies have examined sources of health information and factors that help or prevent access to it, the vast majority were conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic.11–16 The preferred means and methods to access health information may change during a public health emergency where social interaction is restricted. This study was conducted at the Mexican consulate in Omaha, Nebraska. The jurisdiction of this consulate encompasses the states of Nebraska and Iowa. Results from previous studies that members of our research team conducted report that the Consulate of Mexico is a place where Hispanics (in particular those of Mexican origin) feel safe, protected, culturally identified, and have a high level of trust, especially those individuals recently arrived to the U.S.13 A Mexican consulate is officially recognized as Mexican soil in a foreign country.17 In this setting, individuals with diverse immigration statuses (including documented, undocumented, and recent arrival) and from different working sectors (including formal and informal jobs) seek consular services. In Nebraska, 80% of the Hispanic population is of Mexican origin.

This paper aims to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the access and acquisition of health information among Spanish-speaking Hispanics. Furthermore, we seek to investigate the potential of technology to deliver health information to this demographic. The study endeavors to offer pertinent insights for the formulation of health promotion and disease prevention strategies tailored to Hispanics, particularly in the context of a post-pandemic era.

2. Methods

In May 2021, we conducted an electronic cross-sectional survey in Spanish with people accessing the services at the Mexican Consulate in Nebraska-Iowa. Our research team has partnered with the Mexican Consulate for over a decade. We decided this setting was ideal for our study because it would also capture the comments of Hispanic individuals who do not regularly attend clinical settings.

Bilingual investigators administered the survey. The investigators approached people in the consulate’s waiting room, briefly introduced the project, and asked them if they could tell them more about the study. Those who said yes were invited to join a separate area within the waiting room to expand on the purpose of the survey and invite them to participate in the study. The Mexican Consulate assigned this specific location in consultation with the principal investigator of our research team to ensure confidentiality and COVID-19 preventive measures.

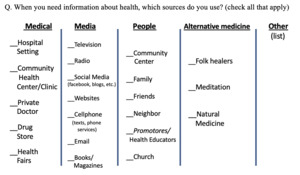

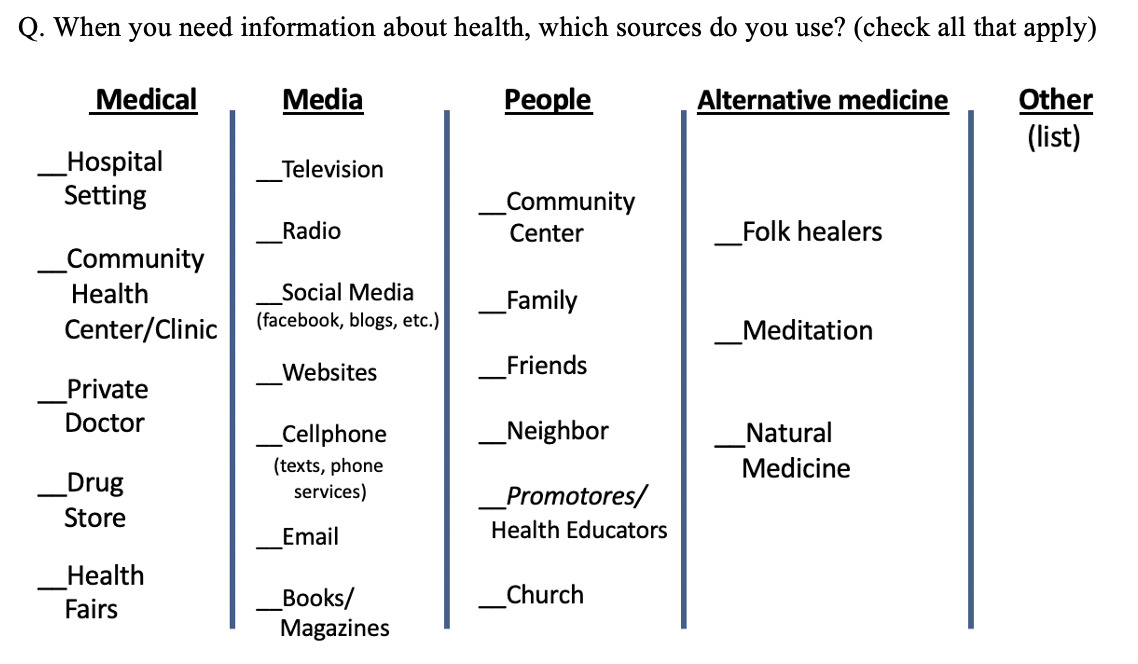

Sources of health information and barriers to obtaining health information were examined by adapting questions from previous studies conducted by Britigan et al. and De Alba et al. in the Midwest.11,13 For example, the participants were shown a table with different options to access health information where they could check “all that apply” (Figure 1). Options for this question included settings such as hospitals, community health centers, private doctors, drugstores, health fairs, and family; media such as television, radio, social media, websites, and newspapers; books and the option of “other” if the participant wanted to indicate an additional source. Input from the staff at the Mexican Consulate in Omaha, faculty members from the University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC), and local community members were included in refining the questionnaire.

The inclusion criteria for study participants were Spanish-speaking Hispanic, ≥ 19 years old, and being able to communicate verbally in Spanish. Prospective participants in the Mexican Consulate’s common areas (entrance and waiting room) were invited to participate in the study. The study received the Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval from the UNMC, and we strictly followed the ethical norms and research IRB procedures to assure participant protection. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize survey questions.

3. Results

Demographics. A total of 307 individuals participated in our survey, 54% male and 46% female (n=164 and 142, respectively; one did not mark the gender). The mean age was 47 years. Regarding education, 50% of the participants went to either elementary (n=79) or middle school (n=79); nine participants never attended school or only attended kindergarten. As to health insurance, 54% (n=165) did not have any kind of health care insurance (Table 1), and nearly two-thirds of participants (n=190) indicated that, in general, their health is either good or excellent.

Sources of health information. The participants could indicate more than one option for where they got their health information. Television was the most common answer (211 participants), followed by social media (206 participants), community clinics (151 participants), website/Google (149 participants), text messages/WhatsApp (148 participants), hospitals (120 participants), and radio (119 participants).

Additionally, respondents were asked, “Do you have access to a computer or a tablet (like iPad, Surface, or Google tablet)?” Fully 63% (n=191) said yes and 95% (n=287) indicated they own a cellphone, and 273 participants use their cellphone to navigate the internet. Around 50% of the total participants (n=151) also indicated that they have participated in a videoconference such as Zoom, Facebook Live, or YouTube Live.

Regarding social media use, participants were asked, “During this COVID-19 pandemic, when you have needed information about health or vaccines, which social media do you use?” Individuals could indicate multiple answers, including “I do not use one.” The most frequent option was Facebook (n=232), followed by YouTube (n=151), WhatsApp (n=87), Instagram (n=62), Twitter/X (n=38), and TikTok (n=29). People who responded that they do not use social media to access health information were 42. Participants were also asked, “How often do you access social media (like Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp or other)?” Almost 75% (n=220) responded that they access it daily, 16% (n=49) at least three times a week, and 3% (n=9) once every week (Table 2).

We also examined if participants read or watched health information in Spanish from countries besides the U.S. (for example, news from Mexico). Eight of every 10 people (n=252) indicated they read or watch health information in Spanish outside of the U.S. Out of these 252 individuals, 99 do so daily, 89 at least three times a week, and 57 once every week.

Barriers to obtaining health information. Participants were provided a list of potential barriers to obtaining health information (Table 2) and could answer yes or no for each option. Among the five most frequent affirmative answers were (1) lack of time (n=114), (2) cost (n=113), (3) language (n=106), (4) lack of insurance coverage (n=97), and (5) “do not know where to get it” (n=87). Additionally, almost one in every four participants (n=70) indicated that “not being allowed by the employer” is a significant barrier, as well as fear of legal status (n=63).

4. Discussion

Health education information has the potential to enhance health outcomes by increasing individuals’ health knowledge, empowering them to make informed decisions, and embracing healthier lifestyles. Our study showed that our participants rely on television and social media such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter/X, and YouTube as their main sources for seeking health information. These results contrast with previous studies before the pandemic by Britigan and collaborators, where medical settings were the most used source by Latinos for health information access.12,13 In recent decades, with the innovation and renovation of technology, electronic devices such as cell phones, tablets, computers, and television screens have become more accessible to the general population. Our results show that among many functionalities, these devices are now considered essential tools for obtaining basic information.

Our findings highlight the need to enhance how health information is communicated through television and social media in the health care sector. It is critical to invest in training health care professionals to effectively engage with these platforms, as media communication requires distinct skills—such as simultaneously delivering health messages while receiving producer instructions and projecting confidence through the camera. Beyond technical proficiency, this training should emphasize research literacy to ensure providers can accurately interpret and disseminate evidence-based information. Given the increasing concerns about misinformation, fostering a health care workforce that is both scientifically informed and ethically committed to accurate communication is critical. While health care professionals play a key role, public health agencies and media organizations must also take responsibility for strategic health communication. For example, their efforts must prioritize proactive communication strategies, ensuring that accurate information is accessible, culturally relevant, and delivered through trusted channels. Additionally, social media platforms and media organizations should have an ethical responsibility to prevent misinformation by promoting credible sources, implementing fact-checking measures, and collaborating with health care experts to amplify reliable content. A coordinated effort among these entities is necessary to build public trust, improve health literacy, and ensure that communities receive timely and accurate health information.

Traditionally, community interventions for disease prevention, such as programs for cardiovascular disease prevention, have been delivered in person, either through one-on-one interactions with health care providers (e.g., counseling sessions for lifestyle modification) or in group settings (e.g., community workshops on healthy eating and physical activity.18,19 While we believe this will continue as one of the most preferred methods for health education, we consider that the COVID-19 pandemic put the use of technology for remote education in an unprecedented position. Our findings support this premise. Hispanic individuals use mobile devices easily and more frequently to navigate the internet and access health information. This is key information for policymakers, researchers, health education experts, and health care leaders interested in reaching out to Hispanic communities in the U.S. Tailoring health information using television and other smart technology like cell phones or electronic tablets is essential.

However, translating health information into Spanish is not enough. We must design and conduct culturally and linguistically appropriate health information. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services underscores this recommendation to all the nation’s health care services by following the National Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) standards.20 While the main objectives of these 15 standards are to advance health equity, improve quality, and help eliminate health care disparities, its first standard, also known as the “principal standard,” calls for the following action: “Provide effective, equitable, understandable, and respectful quality care and services that are responsive to diverse cultural health beliefs and practices, preferred languages, health literacy, and other communication needs.” Therefore, we recommend following the CLAS standards and considering using a systematic approach to develop culturally tailored information, and throughout the development process, we recommend including the input of community members to whom the information will be given.

Our study highlights that some Hispanic communities in the U.S. access health information from Spanish-language sources outside the country, with 83% of participants reporting this practice. This trend may be driven by the increasing use of social media and a preference for culturally tailored information that resonates with their experiences. Particularly among Hispanics born and raised outside the U.S., reliance on familiar or trusted media from their countries of origin could influence health beliefs and decision-making. This finding underscores the need to analyze how other countries effectively deliver health information and identify culturally relevant strategies that may enhance communication efforts in the U.S. Future research should explore whether this trend persists across different Hispanic subgroups with different levels of acculturation and media consumption patterns.

Our findings are consistent with previous studies regarding health information barriers for Hispanics in the U.S.15,16 The most frequently reported barriers to accessing health information included cost, language barriers, lack of health insurance coverage, and uncertainty about where to obtain reliable information. These barriers are modifiable, and existing resources can help mitigate their impact. We recommend that health care providers and organizations adopt a proactive approach to identifying and addressing these obstacles to improve health information accessibility. These efforts should not be limited to populations already engaged with health care services but should also extend to those who remain underserved and disconnected.

Our study has some limitations. Although most participants in this study were of Mexican origin—the largest Hispanic population group in the U.S. and the Midwest—we acknowledge the diversity within the broader Hispanic community. Our findings may not fully capture variations in health information-seeking behaviors across different subgroups, which can be influenced by factors such as country of origin, acculturation level, and length of stay in the U.S. Future research should examine whether similar patterns are observed among other Hispanic subgroups to provide a more comprehensive understanding of health information access within this diverse demographic. Additionally, this study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, a period of increased health information demand. As a result, information-seeking behaviors and perceived barriers could differ in non-emergency contexts. Another limitation is that we did not assess individuals younger than 19 years old. Younger populations may have different ways to seek and engage with health information available.

Despite these limitations, this study provides essential information about how Spanish-speaking populations in the U.S. interact and perceive health care resources. In summary, this study highlights the key role of technology and media in delivering health information to Hispanics in the U.S., particularly during public health emergencies and potentially in the post-pandemic era. For this reason, we recommend increasing the representation and training of health providers using television and social media to engage with audiences who are considered “hard to reach,” such as Hispanics, and communicate promptly during times of health emergencies. Smart technologies can be strategically used to engage with Hispanic communities in health promotion and disease prevention interventions and may reduce or eliminate barriers to accessing health information like the ones reported in this paper. We also recommend that health organizations consider adopting and implementing strategies, such as the CLAS standards in health care services from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, to advance health equity, create a safe space for minority populations, and improve quality services for all.