Introduction

In general, community power can be defined as the capability of individuals or groups to influence how both public resources (such as governmental funds and services) and private resources (including economic opportunities and social amenities) are distributed within a community.1 This encompasses the capacity to shape decisions and policies that allocate resources to address community needs and priorities. Community power leverages various forms of influence, such as advocacy, grassroots organizing, and participation in decision-making processes, to ensure that resources are allocated equitably and effectively to benefit the entire community. It underscores the dynamic interaction between formal governance structures and informal networks, aiming for inclusive and responsive approaches that promote community resilience, equity, and sustainable development.

The historical context of inequities in communities is rooted in longstanding systemic injustices, such as voter suppression,2 housing segregation,3 and wage discrimination,4 which have perpetuated social inequalities based on race, class, and gender. These injustices have created enduring barriers to equitable access to resources and opportunities, further entrenching disparities. These historical inequities form the foundation for the need to foster community power. By building collective agency and leadership, the Community Power Model seeks to counteract these legacies, enabling marginalized communities to challenge and dismantle structural systems of oppression.5 It emphasizes the importance of fostering leadership from within communities most impacted by these inequities to drive transformative change.6

Community power can arise from various sources that include networking and building relationships with influential individuals and organizations, demonstrating large numbers of supporters to validate ideas, offering rewards like recognition or financial support, and from personal traits such as charisma and leadership abilities. Legitimate power derived from formal positions or titles, and expertise and control of information, are also crucial sources of influence. However, coercion, involving negative tactics like intimidation, is seen as less acceptable in contemporary contexts. By understanding and strategically combining these sources of power, communities can enhance the effectiveness of efforts and initiatives.7

A central approach to community power building involves fostering a cohesive constituency that bridges diverse lived experiences. This strategy cultivates an awareness that individual challenges are interconnected with broader systemic issues, mobilizing communities across diverse demographics—including race, class, gender, age, abilities, and cultures—to collaborate toward improving their lives and neighborhoods. At its core, community power aims to cultivate collective agency, emphasizing that united efforts can drive significant change at the community level and contribute to systemic transformations. Ultimately, the Community Power Model seeks to empower those most affected by systemic inequities to advocate for themselves and their communities, ensuring that power is shared more equitably, and decisions are made in a way that benefits all.8

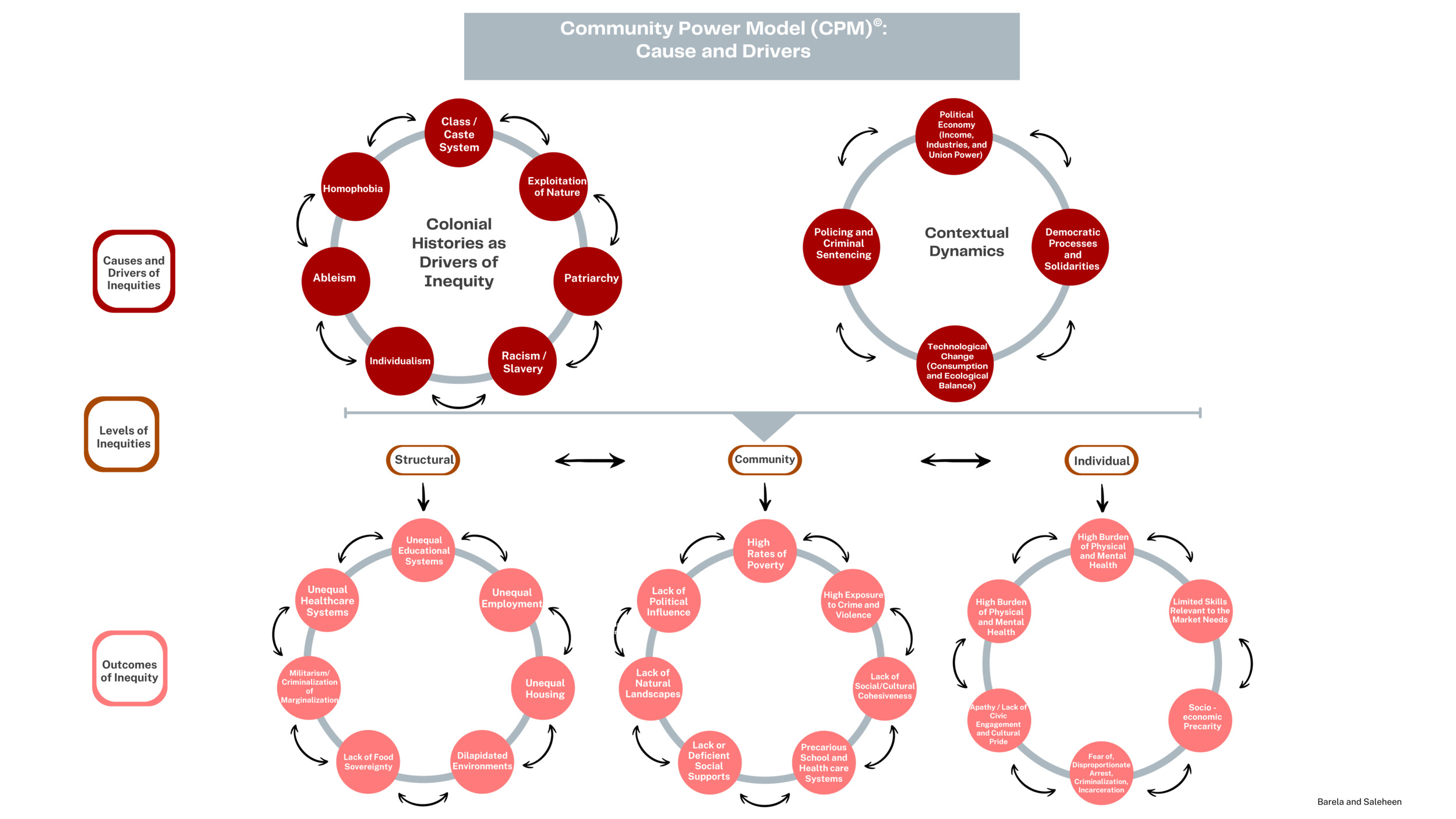

Causes and Drivers of Inequity

The interconnectedness of race, class, gender, ability, and sexuality, rooted in historical legacies, socio-economic structures, and systemic biases, creates a complex web of disadvantage that transcends individual experiences of oppression. It is essential to understand that these issues do not exist in isolation, but rather intersect and overlap, producing unique and compounded effects for individuals who are positioned at the intersection of multiple marginalized identities.

For instance, colonial exploitation of natural resources has often gone hand-in-hand with the subjugation of indigenous peoples and the systemic marginalization of local communities. These groups continue to bear the brunt of environmental degradation, exacerbating health disparities and limiting economic opportunities, especially for communities that are geographically and economically dependent on the land for survival.9

Simultaneously, the persistence of class and caste systems, particularly in regions like South Asia, serves to reinforce social hierarchies that intertwine with gendered and racial inequities. Lower-caste individuals, often marginalized based on both caste and gender, are doubly disadvantaged in terms of access to education, employment, and economic mobility.10 This is a direct manifestation of intersectionality, as the overlapping systems of caste and gender restrict opportunities for specific groups, reinforcing poverty and limiting social mobility. Similarly, patriarchal norms, which dictate limited access to education and political participation for women, are not only a gender issue but also a class issue, as women from lower socio-economic backgrounds face compounded barriers.11 These gendered and class-based disadvantages are often compounded by racism and ableism, which further exclude women of color and disabled individuals from full societal participation.

In parallel, racism remains a pervasive force in perpetuating inequities, particularly for racial minorities whose access to health care, education, and employment is consistently undermined by discriminatory policies and practices. Racism intersects with other factors such as class and disability, creating additional barriers to social mobility and health equity. For example, Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) are disproportionately impacted by chronic health conditions and poor health care outcomes, which are deeply tied to systemic biases in both health care systems and economic structures.12 This illustrates how race interacts with broader socio-economic and environmental factors to compound inequalities.

Similarly, the privileging of able-bodied individuals intersects with other forms of discrimination, such as racism and classism, to exclude disabled individuals from fully participating in society. The compounded effects of ableism on marginalized communities are particularly evident in employment and health care access, where individuals with disabilities, particularly those from racial and class-based minorities, face compounded barriers that limit their opportunities for economic independence and equitable health care.13

Furthermore, individualistic values, which prioritize personal independence over communal support, exacerbate societal divisions by overlooking the importance of collective action in addressing systemic disadvantages. The individualization of social problems fails to account for the structural factors that sustain inequality, thus hindering broader efforts to build social cohesion and equity.14 This is particularly evident when attempts to solve systemic issues focus solely on individual behavior change (such as personal responsibility in education or health care) without addressing the broader social and economic systems that perpetuate these disparities.

Homophobia also intersects with other forms of oppression to sustain discrimination against LGBTQ+ individuals. The compounded stigma faced by LGBTQ+ people of color, for instance, is linked to poorer mental health outcomes, limited access to support services, and discrimination in the workplace and health care systems.15 These individuals are not only discriminated against for their sexual orientation or gender identity but also face compounded disadvantages based on race, gender, and socio-economic status, further entrenching inequities. In summary, intersectionality provides a critical lens through which we can understand how multiple forms of oppression and marginalization intersect to create unique and compounded forms of disadvantage. These interconnected themes demonstrate that inequities cannot be addressed in isolation. They must be understood as multifaceted and interdependent, demanding comprehensive approaches that acknowledge and address these overlapping structures. By recognizing how factors such as race, gender, class, ability, and sexuality intersect and compound one another, we can develop more nuanced, inclusive, and effective policies and interventions that address the root causes of systemic inequities and promote long-lasting social justice.

Levels of Inequity

In examining inequities across structural, community, and individual levels, it is evident that systemic challenges faced by marginalized populations create profound disparities that often intersect and amplify each other, perpetuating cycles of disadvantage.

Structural Inequities

At the structural level, health care disparities provide a stark example of systemic inequity. Marginalized populations frequently experience unequal access to quality health care services, leading to poorer health outcomes.12,16 For instance, Black Americans are more likely to face delays in treatment, receive lower-quality care, and experience higher mortality rates from chronic diseases like hypertension and diabetes.17,18 These disparities are the result of longstanding systemic biases that underfund hospitals in marginalized areas and lack culturally competent care.19 This structure perpetuates health inequities across generations, contributing to poorer physical and mental health outcomes that prevent individuals from reaching their full potential.20

Similarly, in many urban school districts, predominantly Black and Latino students attend underfunded schools with limited resources, including outdated textbooks, overcrowded classrooms, and insufficient access to extracurricular activities.21 This stark disparity in educational resources affects academic performance and limits opportunities for advancement, reinforcing cycles of poverty and inequality. Discrimination in employment and housing also compounds these inequities, where Black and Latino individuals often face racial biases in hiring practices or are excluded from housing markets, further limiting their socio-economic mobility.22 Food insecurity, disproportionately affecting low-income communities, is another systemic issue that reinforces inequities, as marginalized populations lack access to affordable, nutritious food, while also experiencing higher rates of criminalization for issues like food theft or homelessness.2,23

Community-level Inequities

Neighborhoods with high concentrations of poverty, often populated by marginalized groups, lack access to quality education, health care, and social services.24 These communities are also more likely to experience high rates of crime and violence, which not only compromise public safety but also undermine community cohesion. For example, areas with high levels of violent crime may lack the resources to support local businesses or community-based organizations, further destabilizing the area.25 As a result, the negative effects of crime and violence create a cycle where community members feel disconnected from one another and the institutions designed to protect and serve them.

Moreover, community instability is compounded by limited social support services, such as mental health care, childcare, and housing assistance, which further disenfranchise individuals from the resources they need to thrive.26 The lack of access to green spaces or recreational areas—critical for mental and physical health—also exacerbates social and environmental inequities, particularly in urban communities where marginalized groups reside. Finally, underrepresentation in political decision-making results in a lack of policies tailored to the needs of these communities, thus perpetuating cycles of disadvantage and leaving communities voiceless in shaping their futures.

Individual-level Inequities

At the individual level, health inequities reflect broader systemic injustices. People of color and individuals in poverty often suffer from poorer health outcomes due to limited access to preventive care, untreated chronic conditions, and higher rates of exposure to environmental toxins. These health challenges not only affect quality of life but also limit socioeconomic opportunities, as individuals are often unable to work or take part in educational programs due to health burdens.27

Additionally, many individuals from marginalized backgrounds face barriers in gaining access to higher-wage employment opportunities, thus limiting their ability to achieve financial stability and contribute meaningfully to economic development, perpetuating cycles of poverty.28

Disproportionate arrest and incarceration rates among people of color, particularly Black men, illustrate the racial biases embedded within the criminal justice system.2,29 The over-policing of these communities leads to frequent criminal records, which then hinder access to employment, housing, and other social services, perpetuating a cycle of disenfranchisement.

Finally, civic disengagement and social isolation at the individual level are often consequences of systemic inequities. Disconnected from their communities due to limited access to services, exposure to violence, or lack of representation in governance, individuals may develop a sense of powerlessness or apathy toward civic participation.30 This disconnection not only weakens individual empowerment but also contributes to broader societal apathy, hindering collective efforts to address inequities and pushing for structural change.

Interconnected Nature of Inequities

Each of these examples—from structural disparities in health care and education to community-level instability and individual health burdens—interacts and reinforces the others. For instance, a child in a low-income neighborhood with limited access to nutritious food and underfunded schools may experience poor health due to food insecurity, limited educational outcomes due to inadequate schooling, and social instability due to community violence.31 These interlocking inequities create barriers that are not easily overcome without comprehensive, systemic interventions that address the root causes of inequality at multiple levels.32

Addressing inequities requires an integrated approach that considers how structural, community, and individual disparities intersect and reinforce each other.33 Without addressing the systemic biases that perpetuate these disparities across all levels, efforts to reduce inequity will remain incomplete. Comprehensive policies, grounded in equity, must target these interconnected challenges and provide resources, opportunities, and protections to the communities and individuals most affected by systemic injustice.34

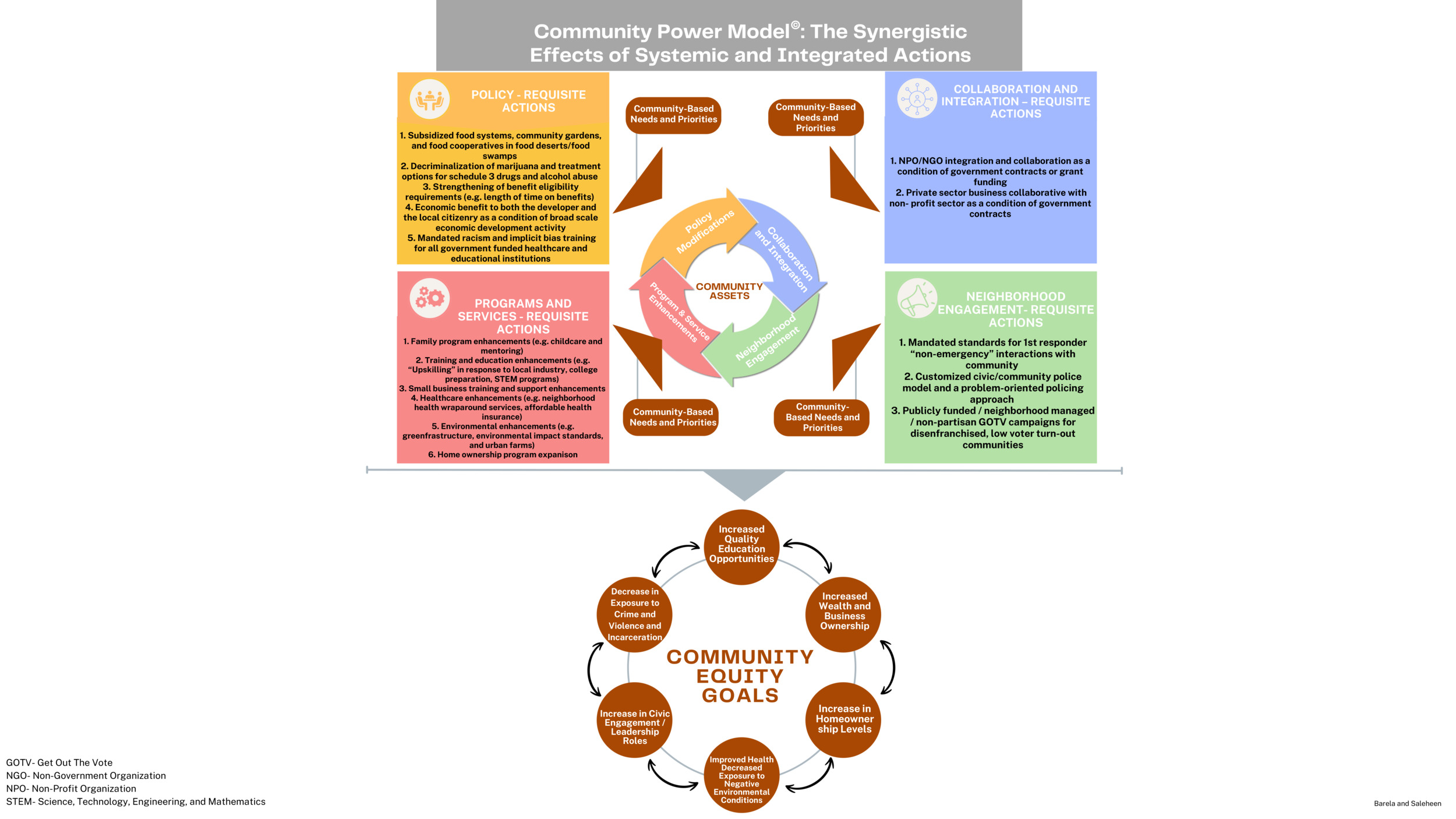

The Synergistic Effects of Systemic and Integrated Actions

Key Systemic Domains:

Policy Modifications

The proposed policy modifications aim to address societal inequities but come with potential challenges that require careful planning and proactive solutions for effective implementation. For example, initiatives such as subsidized food systems and community gardens, while helpful in alleviating food insecurity, face sustainability issues, limited accessibility, and challenges with nutritional education. These can be addressed through local partnerships, ongoing funding, mobile food options, and nutrition programs.33 Similarly, decriminalizing marijuana and expanding substance abuse treatment may create regulatory gaps, stigmatization, and disparities in access to care, particularly in rural or low-income areas. Policymakers can mitigate these challenges by implementing equity-focused regulations, investing in community-based treatment options, and expanding access to care.34 Strengthening benefit eligibility requirements may unintentionally create administrative barriers or perpetuate biases, but these issues can be addressed through regular evaluation, streamlined application processes, and implicit bias training for administrators.32 Economic development projects, if not carefully planned, could lead to displacement and limited benefits for local residents, especially marginalized communities. Anti-displacement measures, local hiring initiatives, and community involvement in decision-making can ensure that development benefits are equitably distributed.31,32 Mandating racism and implicit bias training, while essential for reducing systemic discrimination, may face resistance and lack effectiveness without long-term commitments, comprehensive training, and proper evaluation. Policymakers can ensure the success of such training by offering varied formats and incorporating community leaders in the design and delivery.17,33

To effectively reduce inequities, policymakers must take a holistic, integrated approach, continuously evaluating the policies’ impact and incorporating community feedback to ensure that the intended outcomes—reduced inequities, social justice, and improved community well-being—are achieved.

Collaboration and Integration

Effective collaboration among public, private, and nonprofit sectors is essential to address complex social challenges and promote equitable outcomes. Multi-sector partnerships, as emphasized by Ansell and Gash,35 pool resources and expertise to implement comprehensive solutions that enhance social cohesion and improve social justice. Funding programs, such as the Pay for Success model36 and the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria,37 incentivize collaboration by linking funding to measurable outcomes. Overcoming collaboration barriers requires aligning goals across sectors, establishing flexible funding mechanisms, and fostering trust through joint decision-making and shared accountability, as seen in the Los Angeles County Homeless Initiative.38 Private sector participation, driven by corporate social responsibility (CSR), can further strengthen collaboration, as demonstrated by the UK’s Big Lottery Fund39 and Unilever’s partnership with the World Wildlife Fund.40 To overcome bureaucratic hurdles, policymakers can simplify procurement and grant processes, as seen in New York City’s Workforce Development Initiative. Engaging communities in the collaborative process, through models like Community-Based Participatory Research,41 ensures that initiatives are grounded in local needs.

By addressing these barriers proactively and ensuring that collaborations are inclusive and well-designed, policymakers can maximize the impact of cross-sector partnerships in tackling social inequities.

Neighborhood Engagement

Community members play a central role in shaping and leading neighborhood engagement initiatives, particularly those focused on improving safety, resilience, and civic participation. Their involvement is essential for ensuring that these initiatives are relevant, effective, culturally appropriate, and foster a sense of ownership and empowerment within the community. When residents take an active role in these initiatives, it can result in stronger relationships with public safety officials, more tailored solutions to local problems, and increased social cohesion. Neighborhood-based policing, for example, emphasizes the importance of police officers working directly with community members to address local concerns, build trust, and solve problems. Community members contribute to developing policing policies, participating in safety initiatives, and identifying local issues, such as crime or infrastructure concerns, which guide law enforcement strategies. This collaboration builds trust, increases the perceived legitimacy of law enforcement actions, and leads to more effective problem-solving. However, conflicting interests and distrust in some areas may pose challenges, which can be addressed by creating safe spaces for dialogue and employing third-party facilitators. Similarly, first responders—such as police officers, paramedics, and firefighters—interact with communities in non-emergency situations, and establishing clear engagement standards ensures respectful and empowering interactions. Community members can provide feedback on how first responders should engage, offer training on local customs, and help improve relationships by fostering empathy and cultural sensitivity. Resistance to change may occur within first responder agencies, but gradual implementation and support through training can help overcome this.

In civic policing models, which prioritize collaborative problem-solving, community members help identify local concerns like youth violence or homelessness and serve as liaisons between residents and law enforcement. This involvement fosters collaborative problem-solving, enhancing public safety and community satisfaction. Similarly, Get Out The Vote (GOTV) campaigns led by community members ensure higher voter turnout, particularly among marginalized populations. By providing culturally relevant information and organizing outreach efforts, residents empower their peers to participate in the electoral process, strengthening civic identity and engagement. Challenges such as voter suppression can be addressed through collaboration with advocacy organizations and legal aid. Ultimately, the active involvement of community members in shaping neighborhood engagement initiatives ensures that solutions are tailored to local needs; fosters stronger, more cohesive neighborhoods; and enhances public safety, trust in law enforcement, and civic participation.

When community members are actively involved in shaping and leading these initiatives, their perspectives—shaped by unique cultural contexts and experiences—play a crucial role in making the initiatives both meaningful and effective. Incorporating cultural sensitivity and trauma-informed practices into these efforts not only fosters stronger relationships between community members and public safety officials but also leads to solutions that are more tailored to local needs and challenges.

Evidence-Based Community Program Enhancements

To critically assess the evidence base for proposed program enhancements within community-driven initiatives, it is crucial to evaluate both the strengths and limitations of the existing evidence supporting such interventions. While evidence-based approaches are vital for ensuring programs effectively address social issues and promote equity, several factors must be considered regarding their application, scalability, and contextual relevance. By incorporating a more nuanced perspective on the evidence base, we can better understand how these program enhancements contribute to equity and community resilience, while also addressing potential gaps or challenges that may arise during implementation.

Family Programs: Enhancing Childcare and Mentoring

Family programs that focus on enhancing childcare and mentoring services are pivotal in supporting families and promoting child development, contributing to long-term stability and well-being. High-quality childcare has been linked to improved cognitive development, and mentoring programs have shown positive effects on academic achievement and social skills.42 However, challenges remain in ensuring these programs are scalable, sustainable, and effectively meet the needs of marginalized communities. Key issues include affordability, availability, and the integration of additional support services, such as tutoring or mental health resources, which are critical for maximizing impact. To enhance the effectiveness of such programs, policymakers must ensure adequate funding, cultural sensitivity, and programs tailored to the unique needs of underserved communities. A comprehensive approach, incorporating resources like health care and housing support, will further improve their long-term success and contribute to advancing equity.

Educational Expansions: Aligning with Local Industry Needs

Programs that align educational expansions with local industry needs, particularly in STEM fields, are essential in preparing youth for careers and addressing workforce disparities. STEM initiatives have demonstrated potential in promoting upward mobility and reducing educational gaps, particularly for underrepresented groups.43 However, the effectiveness of such programs can be undermined by barriers like underfunded schools, a lack of qualified teachers, and limited access to technology. Additionally, the assumption that aligning education with local job markets will automatically create employment opportunities is often overly optimistic, especially in volatile economies. To enhance these initiatives, policymakers should foster partnerships between educational institutions, local businesses, and government agencies. Investments in infrastructure and teacher training are crucial to ensuring that all students, regardless of background, have access to high-quality STEM education, contributing to greater economic mobility and reducing disparities.

Expanding Small Business Training and Support

Small business training and support programs are vital for fostering entrepreneurship, creating jobs, and strengthening economic resilience, especially in underserved communities. These programs provide critical resources, mentorship, and knowledge to aspiring entrepreneurs, helping them navigate challenges and build successful businesses. However, the effectiveness of such programs is influenced by local economic conditions, access to capital, and infrastructure. Small businesses in low-income areas also face additional barriers, such as limited customer bases and competition from larger businesses, which can undermine the long-term success of these initiatives. To increase the success of small business training programs, policymakers must ensure access to microloans, mentorship, and networking opportunities. Additionally, small business programs should be culturally sensitive and responsive to the economic conditions of the communities they serve, ensuring long-term growth and sustainability.44

Health Care Sector Enhancements: Accessibility and Quality of Care

Improving health care access, particularly in underserved areas, is critical to enhancing health outcomes and reducing disparities. Programs that provide integrated care, including wraparound services for both physical and mental health, have proven effective in addressing the social determinants of health.45 However, challenges remain in expanding capacity, addressing workforce shortages, and reducing long wait times. Moreover, while expanding insurance access has improved some health outcomes, it does not fully address root causes such as poverty or housing instability, which continue to contribute to health inequities. Policymakers must integrate health care initiatives with broader social support programs, ensuring that health interventions are connected with housing, education, and employment services. Addressing health care workforce shortages and promoting preventive care can help reduce long-term health disparities, contributing to better overall community well-being and resilience.

Environmental Enhancements: Green Infrastructure and Urban Farming

Environmental improvements, such as green infrastructure and urban farming, not only promote sustainability but also enhance community resilience, health, and economic opportunities. Green spaces and urban farms improve air quality, provide fresh food to underserved communities, and foster social cohesion.46 However, these programs face challenges, such as the risk of gentrification in urban areas, where green development can lead to the displacement of low-income residents. Furthermore, the effectiveness of these initiatives in achieving social equity depends heavily on local context and the involvement of community members in planning and managing projects to ensure long-term success. Policymakers should design environmental programs with protections against displacement, ensuring that vulnerable communities benefit from green infrastructure and urban farming without negative side effects. By engaging residents directly in the planning and management of such projects, these initiatives can ensure that the benefits are shared equitably, contributing to long-term community resilience.

Homeownership Programs: Housing Affordability and Stability

Homeownership programs are often seen as a means to promote economic stability and empowerment, especially in low-income communities. These programs, through financial literacy training, down payment assistance, and affordable mortgage options, have successfully increased homeownership rates, contributing to improved health, education, and economic outcomes.47 However, housing affordability remains a significant issue, particularly in high-demand urban areas. Without addressing broader housing supply issues, these programs may fall short of ensuring long-term stability. Furthermore, marginalized groups may struggle to realize the economic benefits of homeownership due to higher debt levels or foreclosure risks. Policymakers should prioritize increasing the supply of affordable housing and provide support for renters alongside homeownership initiatives. Ensuring that homeownership programs include long-term financial education and protections against predatory lending practices is crucial for ensuring success and stability for families in the long term.

Customization and Identification of Community Assets

Effective community development hinges on a deep understanding and appreciation of each community’s distinct culture, strengths, and resources. It is crucial to recognize that every community possesses unique assets that can serve as a foundation for sustainable, equitable development. Communities can identify and leverage these assets through participatory approaches, ensuring that interventions are culturally relevant, community-led, and aligned with local needs.

For instance, communities can draw on their cultural heritage as a powerful asset. Local traditions, values, and practices can promote social cohesion, preserve identity, and create economic opportunities. One example of this is the use of traditional knowledge in environmental conservation, where Indigenous communities have successfully employed time-honored practices for sustainable land management. In such cases, respecting and integrating indigenous knowledge into broader policy frameworks can result in more culturally sensitive and effective interventions.48

Social capital, which refers to the networks of relationships and trust within a community, is another critical asset that can drive equitable development. By fostering collaboration and collective action, communities can work together to address local challenges. For example, neighborhoods can form grassroots organizations to advocate for improved infrastructure or public services, ensuring that development efforts reflect their needs and aspirations. This participatory approach not only builds trust but also strengthens the capacity of community members to lead change.

Moreover, community-based organizations, churches, and local civic institutions play a central role in leveraging community assets. These institutions can facilitate dialogue, mediate conflicts, and help channel resources into local development efforts. Empowering these organizations and their leaders to take an active role in governance ensures that interventions are community-led, culturally relevant, and responsive to the specific context of the neighborhood.

Another key approach is integrating local economic assets into development strategies. For example, small local businesses or cooperative enterprises can become engines for economic growth. Communities can promote business incubators or microfinance initiatives that provide local entrepreneurs with the tools and resources to thrive. This not only enhances economic opportunity but also strengthens local ownership of the development process, ensuring that the benefits of growth are distributed equitably within the community.49

Additionally, evidence-based programs can be tailored to address specific local challenges. For instance, in areas with high rates of chronic illness, community health programs might be designed around local health care knowledge, while also incorporating broader health initiatives. A participatory approach in designing these interventions ensures that they are culturally appropriate and address the unique health needs of the population.

Ultimately, recognizing and leveraging community-specific assets requires a shift away from top-down development approaches. Instead, development strategies should empower communities to identify and utilize their own resources, ensuring that interventions are grounded in local values and priorities. By engaging communities as active participants in the development process, policymakers can craft more effective, resilient solutions that reflect the true needs and aspirations of the people they are meant to serve.

Systemic Integration

To effectively decrease inequities in communities, integrating four essential domain—public policy modifications, collaboration across sectors, neighborhood engagement, and evidence-based community services—is a crucial element to the Community Power Model. Each domain plays a distinct yet interconnected role in addressing disparities and promoting equity for marginalized populations, supported by scientific research and evidence.

Integration across these domains is imperative to maximize impact and achieve sustainable equity. By aligning policies, collaborations, neighborhood engagements, and evidence-based services under a unified value system, communities can effectively address systemic inequities. This integrated approach ensures that efforts are coordinated, resources are optimized, and interventions are responsive to the diverse needs and priorities of marginalized groups.

In summary, a holistic approach that integrates public policy, sector collaboration, neighborhood engagement, and evidence-based services is essential for achieving equity. This integrated strategy not only enhances the effectiveness of interventions but also promotes inclusive governance and community resilience, contributing to lasting social change.

Community Equity Goals

Achieving equity across structural, community, and individual levels necessitates a strategic and persistent approach, exemplified by the Community Power Model, which posits that sustained efforts spanning two generations can effect transformative societal changes. Quality education plays a pivotal role in breaking the cycle of inequity by enhancing academic outcomes and socio-economic mobility.21 Similarly, increasing wealth and promoting business ownership among marginalized communities contribute significantly to reducing income disparities and fostering economic stability.50 Homeownership programs, known to enhance wealth accumulation and neighborhood stability, are crucial indicators of economic empowerment and community investment.51 Improving health outcomes and reducing exposure to negative environmental conditions through accessible health care and environmental improvements are essential for enhancing overall well-being and mitigating health disparities.9,16 Civic engagement and leadership roles empower individuals to participate in decision-making processes, advocate for equitable policies, and contribute to community development.52 Addressing systemic injustices related to crime and incarceration through community safety initiatives and criminal justice reforms is critical in reducing crime rates and minimizing the disproportionate impact on marginalized populations.2,29 Implementing the Community Power Model requires coordinated efforts across policy, collaboration, neighborhood engagement, and evidence-based interventions to comprehensively address these facets and foster sustainable changes that promote equity and social justice for future generations.

Measurable Indicators for Equity Goals

To track and evaluate progress toward equity goals effectively at structural, community, and individual levels, it is essential to establish clear, measurable indicators that capture the multifaceted nature of equity. These indicators should be aligned with the specific objectives of the Community Power Model and the broader vision of social justice.

For quality education and socio-economic mobility, progress can be assessed through indicators such as graduation rates, standardized test scores, college enrollment rates, and workforce participation post-graduation. Tracking progress involves conducting longitudinal studies, monitoring academic achievement, and administering community surveys on educational access and post-graduation outcomes. Measuring changes over time in graduation rates or standardized test scores, particularly in targeted communities, can provide concrete evidence of progress.

Economic stability and wealth-building can be evaluated using indicators like income inequality metrics, small business creation, access to capital, homeownership rates, and median household income. Evaluating these indicators involves conducting economic impact assessments, tracking community wealth-building initiatives, and monitoring small business growth and workforce development program outcomes. By analyzing trends in income and wealth disparities, the success of wealth-building initiatives can be assessed.

Homeownership and neighborhood stability can be gauged through indicators such as homeownership rates among marginalized groups, property values, neighborhood crime rates, and housing satisfaction. This can be tracked through housing audits, resident satisfaction surveys, and tracking changes in homeownership rates, particularly among underrepresented communities. Additionally, surveys on neighborhood satisfaction and housing security can indicate the effectiveness of programs designed to promote homeownership.

For health and environmental improvements, indicators such as life expectancy, chronic disease rates, air quality, and access to health care can be used. This progress can be tracked through health outcome monitoring, including rates of chronic illness and life expectancy, as well as environmental assessments on air quality and access to clean water. Community health surveys focusing on health care access, environmental health, and social determinants of health can also provide valuable data on improvements in health and environmental conditions.

Civic engagement and leadership roles can be assessed through indicators like voter turnout, participation in local governance, volunteering rates, and leadership roles in community organizations. Tracking progress involves measuring voter engagement, conducting surveys on civic participation, and monitoring involvement in local governance and leadership development in community organizations. Regular assessments of civic engagement, such as participation in decision-making processes, can be used to measure community empowerment.

Finally, community safety and criminal justice reform can be evaluated through crime rates, arrest and incarceration rates, racial disparities in criminal justice processes, and community policing effectiveness. Progress in this area can be tracked by conducting crime and safety audits, analyzing arrest and incarceration rates, particularly focusing on racial disparities, and evaluating community policing models. Surveys on perceptions of safety and law enforcement-community relations can also provide insight into progress toward greater community safety.

Tracking Progress Over Time

To ensure that these equity goals are being achieved, progress can be tracked through several methods. First, regular data collection is necessary, involving both quantitative and qualitative data gathered through surveys, interviews, and statistical analyses. It is essential that this data is disaggregated by race, income, gender, and other demographic factors to ensure that equity gaps are being addressed. Engaging communities in the evaluation process is also crucial; this can be done through feedback and insights from community members on the effectiveness of policies and initiatives. Participatory action research methods can be particularly useful in ensuring that communities play an active role in tracking progress. Longitudinal studies should be used to assess changes over time, tracking outcomes across multiple generations to capture the long-term impact of equity initiatives. Additionally, public reporting of progress through regular updates helps maintain transparency, fosters ongoing community engagement, and ensures accountability.

Examples and Outcomes

Several initiatives have successfully used measurable indicators to track progress in equity goals. For example, the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Opportunity Task Force tracked educational and economic mobility for marginalized populations, reporting improvements in high school graduation rates and increases in homeownership among Black residents over a period of five years.53 Similarly, the Homeownership for All program in San Francisco showed a measurable reduction in wealth disparities and an increase in homeownership among low-income communities over the course of 10 years.51 In Baltimore, health outcomes were improved through environmental and health care interventions, with reductions in asthma rates linked to better air quality measures in low-income neighborhoods.9 These examples demonstrate how measurable indicators and effective tracking mechanisms can lead to tangible improvements in equity.

By employing rigorous data collection, community involvement, and continuous evaluation, policymakers and communities can ensure that equity initiatives are successful, sustainable, and impactful. This process also allows for necessary adjustments and improvements, ensuring that the desired long-term societal transformations are achieved.

Conclusion

It is time for policymakers, community leaders, organizations, and individuals to take bold, collective action to dismantle the systemic inequities that continue to divide our society. The Community Power Model offers a strategic framework that places marginalized communities at the center of solutions, empowering them to drive change. By embracing this model, we can create a future where every individual, regardless of background, has access to the opportunities, resources, and services they need to thrive. We must work together to implement policy modifications that promote fairness in health care, education, employment, and housing, ensuring cross-sector collaboration to pool resources and expertise for sustainable, equitable outcomes. Neighborhood engagement initiatives should become the norm, with community members not only heard but leading the way in crafting solutions that work for them. It is essential to commit to evidence-based, culturally relevant, and trauma-informed approaches that address each community’s unique challenges.

Now is the time for action. Together, we can tackle the root causes of inequity, build community resilience, and create pathways to long-term social and economic mobility. The shift toward a more equitable society requires a collaborative effort from all of us — policymakers, organizations, and community members — working toward a shared vision. Let us commit to a future where justice, equity, and inclusion guide every decision and every policy, ensuring that every individual has the chance to flourish in a world that works for all.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our sincere gratitude to Mr. Christopher Barela for his insightful discussions and valuable suggestions, which have significantly enhanced the quality of this manuscript.

We are also grateful to Dr. Linda Sprague Martinez and Dr. Douglas Bruggefor their thoughtful comments and suggestions during the review process. Their feedback has been invaluable, and we sincerely appreciate their contributions.