Introduction

Health care disparities within the Latino/Hispanic/Spanish + (LHS+) population remain a critical issue, particularly in the realm of surgical-oncological outcomes. However, the Hispanic Paradox phenomenon suggests that LHS+ experience better health outcomes despite socioeconomic disadvantages. This phenomenon does not fully capture the complexities and challenges faced by this population, specifically in surgical-oncological care. Numerous studies have highlighted disparities in access to timely treatment, postoperative complications, and survival rates among LHS+ patients undergoing both general and oncological surgical procedures. Factors such as limited English Proficiency (LEP), socioeconomic status, health care accessibility, and cultural barriers contribute to delays in diagnosis, restricted treatment options, and higher rates of complications. Additionally, LHS+ patients often present with more advanced disease stages, reducing eligibility for curative interventions such as surgical resection and transplantation. These disparities are particularly evident in oncological care, where LHS+ patients experience longer wait times for surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy, as well as increased rates of major complications postoperatively. This manuscript aims to analyze these disparities in-depth, providing a clearer understanding of how socioeconomic and systemic factors impact surgical-oncological outcomes within the LHS+ community. By exploring disparities in treatment access, disease progression, and surgical complications, this work seeks to contribute to the development of targeted interventions that address health care inequities and improve outcomes for LHS+ patients.

It is equally important to acknowledge the limitations of the current evidence base. Much of the existing literature on surgical-oncological disparities in LHS+ populations derives from retrospective analyses, single-center cohorts, or studies limited by small sample sizes. These methodological factors increase the risks of selection bias and limit the generalizability of findings across diverse LHS+ subgroups. Acknowledging these limitations is important, as they may obscure the true extent of disparities. Future research may therefore prioritize prospective, multi-center designs with sufficient statistical power to better characterize inequities in surgical-oncological outcomes.

Methods

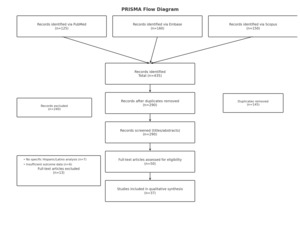

A structured search of PubMed, Embase, and Scopus was conducted to identify studies published between January 1, 2023, and May 31, 2025, that examined disparities in surgical oncology among LHS+ populations. The search combined controlled vocabulary and free-text terms for LHS+ groups, surgical oncology, and disparities, and was restricted to publications in English. Inclusion criteria were peer-reviewed original studies (RCTs, cohort, case–control, cross-sectional, registry/database, or systematic reviews) reporting surgical or oncologic outcomes among LHS+ patients, including subgroup analyses. Exclusion criteria were nonoriginal articles, animal or laboratory studies, studies without disaggregated outcomes for LHS+ populations, and conference abstracts or gray literature. After removing duplicates, titles and abstracts were screened, followed by full-text review, with eligible studies incorporated into the synthesis. The study selection process is summarized in Figure 1. The complete search strategies for PubMed, Embase, and Scopus are provided in Appendix 1.

Disparities in Outcomes

Surgical Outcomes

Although the Hispanic Paradox has often been invoked in discussion of health disparities within the LHS+ population, it should not be viewed as a definitive conclusion in outcomes research. Numerous findings indicate disparities in the LHS+ community’s health outcomes, particularly in surgical-oncological settings. This manuscript focuses on surgical-oncological outcomes, aiming to shed light on these disparities and more equitable health care services for the growing LHS+ population.

Evidence suggests the existence of disparities in surgical outcomes. Studies consistently show that LHS+ patients undergoing low to high-risk surgeries face higher odds of postoperative complications compared to their non-Hispanic white counterparts (NHW).1 Moreover, when considering a broader perspective, concerning patterns emerge that transcend intersectional boundaries. For instance, in comparison to NHW patients, Black patients are more likely to experience readmission and reoperation, while LHS+ patients face elevated odds of major and minor complications.2 While this manuscript focuses on highlighting disparities within the LHS+ population, acknowledging disparities across demographic groups is essential to obtain a comprehensive understanding of how surgical outcomes vary.

Sanford, et al., report significant disparities in the likelihood of undergoing surgery among different ethnic groups, particularly LHS+, African-American, and Asian children, when compared to NHW children.3 LHS+ children have a higher probability of requiring emergent or urgent surgical interventions.4 This discrepancy may stem from various socioeconomic factors that hinder patients from seeking timely medical treatment upon the onset of symptoms. Notably, the higher likelihood of emergent and urgent surgeries in LHS+ children supports this notion.5 Several factors contributing to the delayed seeking of care among LHS+ patients include socioeconomic status, limited access to health care, limited English proficiency, and others later discussed. These factors present significant challenges for LHS+ in accessing timely care, thereby resulting in treatment delays and, subsequently, poorer outcomes.

Limited English proficiency (LEP) profoundly shapes when and how patients seek medical attention, serving as a socio-cultural barrier to early detection and treatment. Studies demonstrate that LHS+ with LEP exhibit significantly worse outcomes in appendiceal perforation cases.4 Higher perforation rates suggest that LEP impacts care-seeking behavior and medical management. Similarly, LHS+ with LEP and moderate-severity appendicitis were less likely to undergo advanced imaging compared to their English-speaking, NHW counterparts.4 These findings highlight LEP as a social determinant of care that extends beyond standard into the surgical field. Although ongoing efforts are being made to bridge the language gap, it is crucial to continue training physicians proficient in multiple languages and who possess an awareness of patients’ cultural intricacies.

The disparities mentioned previously address those that are found in nononcologic surgical cases. Disparities are also observed when we analyze literature specific to surgical oncology and oncologic treatment as a whole. Said disparities are present in multiple aspects that lead to worse outcomes in the LHS+ population.6 These include increased time to treat, curative intent procedures, and lastly, postsurgical status itself.

LHS+ patients experience disproportionately longer times from the onset of symptoms to initiation of treatment. Evidence indicates that LHS+ patients had the longest time to surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy when compared to NHW patients.7 For example, Ahmed, et al. demonstrated that LHS+ women experience delays in breast cancer treatment despite breast cancer being the leading cause of cancer-related death in LHS+ populations.8

Postoperative reports of surgical outcomes in cases of breast cancer patients also highlight significant differences for LHS+ patients when compared to their NHW counterparts.9 Firstly, LHS+ women undergo breast-conserving surgery at lower rates than their NHW counterparts.10 This is due to lower rates of screening and diagnosis delay, which leads to advanced disease presentation.10 Even when opting for reconstructive surgery, LHS+ women face higher complication rates postoperatively, including higher rates of partial mastectomy flap necrosis (p=0.043), arterial (p=0.009), and venous insufficiency (p=0.026) during microvascular reconstruction.11 These problems arise due to a higher rate of comorbidities seen in LHS+ patients.11

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represents another major cancer burden in the LHS+ population. As of 2020, the LHS+ population has shown the highest incidence of HCC, surpassing that of the Asian population, which held the highest incidence previously.12 For context, LHS+ patients are at least 2.5 times more likely to present with HCC than their NHW counterparts.13 Surgical resection of localized tumors and transplantation are the gold standards for treatment of this malignancy.14

Both surgical resection and liver transplantation are effective treatment modalities; however, outcomes differ substantially. Five-year survival rates approach 70% following liver transplantation, compared with approximately 50% after surgical resection.15 Tumor recurrence is also markedly lower among patients who undergo successful transplantation.15 Nevertheless, eligibility for transplantation is limited, and not all patients qualify, emphasizing a critical barrier to optimal outcomes. Eligibility for transplantations follows the Milan criteria, LHS+ patients tend to present with more advanced tumors that are nonresectable and exclude them from transplantation by falling outside the Milan criteria. Overall, LHS+ patients were less likely to fall within Milan criteria (26% vs. 38%; P < 0.0001) and were less likely to be treated with resection (9% vs. 13%; P = 0.03) or transplantation (8% vs. 19%; P < 0.0001) when compared to NHW.13 However, LHS+ patients had a median overall survival of 1.4 years (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.22-1.56), which was similar to that of NHW patients (1.3 years; 95% CI, 1.26-1.41; P = 0.07).16 In this instance, we may see the influence of the Hispanic Paradox in reported outcomes.

These results raise concerns, specifically highlighting a gap between presentation and outcomes. A persistent gap remains in our understanding of overall outcomes, likely influenced by the Hispanic Paradox and the multiple factors that may contribute to perpetuating it. This gap must be studied in order to highlight said specific barriers that are affecting overall outcomes in these patients. Thankfully, stratified studies are becoming more commonplace, and the ability to ascertain the particular needs of each population is becoming common. One of the central aims of this manuscript is to highlight these issues and to allow for increased comprehension, which can lead to highly targeted studies that address these disparities.

Oncology Outcomes

Epidemiology and Disparities

For many LHS+ families across the United States, cancer is not simply a medical condition but an ever-present reality. While heart disease remains the leading cause of death among the general U.S. population, cancer claims more lives in LHS+ communities than any other disease.17 This striking difference reveals deep-seated disparities that continue to shape health outcomes for LHS+ populations.

Prostate cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer among LHS+ men (22%), followed by colorectal cancer (11%) and lung and bronchus cancer (7%), while breast cancer is the most common among LHS+ women (29%), followed by uterine corpus cancer and colorectal cancer (8% each). Although LHS+ individuals have a slightly lower lifetime probability of developing cancer (36% for women and 37% for men) compared to NHW (41% for men and 40% for women), they face higher cancer mortality rates in certain age groups.17 For instance, mortality rates are higher among LHS+ males aged 15 to 29 years old (IRR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.16-1.29) and LHS+ females aged 25 to 29 (IRR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.04-1.33) when compared to NHW.17

Despite medical advancements, the fight against cancer has not demonstrated equal outcomes. Between 2010 and 2019, cancer mortality declined for LHS+ men (by 1.6% per year) and women (by 0.9% per year), mirroring the progress seen in NHW populations (1.85% for men and 1.5% for women).11

Although cancer mortality has declined overall, disparities persist. For example, from 1990 to 2019, breast cancer mortality has dropped by 29% among LHS+ women, but NHW women have seen a steeper 42% decline.17 Furthermore, survival rates tell a concerning story, as the five-year relative survival rate for breast cancer is 92% for NHW women, while the rate for LHS+ women is lower at 88%, based on cases diagnosed between 2011 and 2017.17 These gaps may not be purely biological but instead reflect disparities in health care access, early detection, socioeconomic factors, and treatment availability.

Puerto Rican men face even steeper challenges. As per data from 2014 to 2018, compared to NHWs, Puerto Rican men experience an 18% higher colorectal cancer incidence and a staggering 44% higher prostate cancer rate.17 These disparities may reflect greater exposure to risk factors, limited access to preventive measures, and differences in health care quality.

For many LHS+ patients, barriers to care mean later-stage diagnoses, more aggressive disease progression, and limited treatment options. Language barriers, financial constraints, and a lack of culturally tailored health care approaches create additional roadblocks, leaving many LHS+ patients with fewer options and worse outcomes.

(Refer to Table 1 and Table 2 for further details.)

Treatment, Risk Factors, and Overall Outcomes

For many LHS+ cancer patients, the challenges extend well beyond diagnosis. Even when treatment is available, disparities in access and quality of care often dictate the course of their disease. One of the most striking examples is HCC, a cancer that disproportionately affects LHS+ communities, with nearly double the mortality rate compared to NHWs.18 This higher burden is driven by nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, alcohol-related liver disease, and chronic hepatitis C, risk factors that are more prevalent among LHS+.13,19 Despite having similar survival rates when treated, LHS+ patients with HCC are less likely to receive immunotherapy and more likely to present at advanced stages, limiting their surgical options as previously stated.13,20 These disparities are not a result of biology but of systemic barriers such as lower insurance coverage, financial strain, and delays in accessing specialized care.21

LHS+ women with breast cancer also face several obstacles, such as socioeconomic barriers often limiting their access to radiation therapy, increasing their likelihood of undergoing mastectomies, and raising their risk of recurrence.22 Yet, when given equitable access to standard chemotherapy, LHS+ women show no significant disparities in treatment completion or outcomes, despite often presenting with higher-grade tumors and at younger ages than their NHW counterparts.23 This highlights a critical reality: when treatment access is equalized, so are survival rates.

Despite these challenges, an intriguing pattern emerges: LHS+ women often demonstrate better survival outcomes than NHW women, even though they are more likely to present with aggressive disease. This paradox has been observed across various LHS+ subgroups and suggests that protective cultural, genetic, or lifestyle factors may contribute to survival advantages. However, disparities in tumor subtype, disease stage at diagnosis, and access to advanced treatment options remain significant.24 Moreover, the country of origin plays a role in breast cancer outcomes, as women from Central and South America and the Dominican Republic have higher survival rates than those from Mexico.25 These variations highlight the need for nuanced, population-specific research when addressing disparities.

Across all cancer types, a common theme emerges: disparities in health care access, whether due to socioeconomic challenges, insurance coverage, or cultural barriers, contribute to later-stage diagnoses and reduced access to advanced treatments. Yet, in some cases, LHS+ patients demonstrate better outcomes than their NHW counterparts. A detailed analysis of said studies is necessary to ascertain if said studies fail to stratify subpopulations, a major issue that contributes to the Hispanic Paradox. When studies generalize across populations, they fail to take into account specifics of each demographic that might explain such paradoxical outcomes. Ultimately, while the Hispanic Paradox suggests certain protective factors that may enhance survival outcomes, the reality of treatment disparities underscores the importance of ensuring equitable access to cancer care. By addressing these disparities through early screening, culturally tailored interventions, and a better understanding of the genetic and environmental factors involved, outcomes for LHS+ patients with cancers such as HCC, breast, and prostate cancer can be further improved. Further breakdown and stratification of outcomes can be found on Table 3.

Disparity Factors and the Hispanic Paradox

Delays in diagnosis and screening

Limited English proficiency (LEP) remains a critical barrier to timely diagnosis and treatment in oncology care, especially among LHS+ patients.26 LEP patients often experience delays in critical screening exams, such as mammograms and colonoscopies, leading to advanced-stage diagnosis of breast and colorectal cancer, respectively.27 These delays occur as patients with LEP are less likely to receive preventative care due to communication challenges and systemic barriers, such as lack of access to interpreters. LHS+ individuals are disproportionately affected, with higher rates of late-stage cancer diagnosis, worse prognosis, and limited access to early intervention.28 Proper cancer staging, crucial for predicting outcomes and determining effective treatment strategies, is often compromised in these cases.

Interventions involving interpreters and multilingual physicians are essential to addressing language barriers and improving cancer care delivery. Additionally, telehealth and telemonitoring present opportunities to enhance perioperative care and access for LEP populations by reducing hospital readmissions and enabling continuous monitoring.29 However, challenges such as low digital literacy and limited access to technology must be addressed to ensure telehealth’s inclusivity and effectiveness for all patients.30 Accordingly, embedding professional interpreters throughout the perioperative pathway, coupled with culturally tailored preoperative education and deployment of community health navigators, represents a critical next step in mitigating these disparities.

Comparison of Mainland U.S. vs Latin American Countries

LHS+ populations in the mainland U.S. and their respective Latin American countries experience distinct disparities shaped by health care access, cultural norms, socioeconomic challenges, cancer progression, and environmental risks. In the mainland, barriers such as limited health care facilities, lower insurance coverage, and delayed treatments significantly hinder early cancer screenings and care, leaving uninsured LHS+ at a pronounced disadvantage compared to insured NHW.31 By contrast, native lands like Cuba and Chile prioritize equitable care through government-funded programs, enabling broader access to screenings, though rural areas still face shortages in specialized cancer services.32 Cultural influences also diverge: in the mainland, norms like “machismo” and “marianismo” delay health care-seeking behaviors,33 while in patient’s respective countries of origin, reliance on traditional health practices may support holistic care but can also postpone diagnosis and treatment. Socioeconomic disparities further widen the gap—low-paying jobs and lack of paid leave in the mainland result in higher rates of missed follow-ups among LHS+,34 whereas programs in countries like Chile and Argentina help alleviate financial burdens through subsidized cancer treatments.35 Cancer progression also highlights stark differences; LHS+ in the mainland are more likely to present with advanced disease stages, as seen in higher rates of late-stage breast cancer among Puerto Rican women living in the U.S. compared to those in Puerto Rico.36 Environmental and lifestyle factors further complicate these disparities: urban LHS+ communities in the mainland often face “food deserts,” leading to higher rates of obesity-related cancers, while native lands benefit from traditional diets yet grapple with cancer risks linked to pesticide exposure in agriculture.37 These overlapping challenges emphasize the need for targeted interventions addressing the unique barriers faced by LHS+ populations in both the mainland and native lands. To address these systemic disparities, policy level interventions such as advocating for Medicaid expansion, ensuring reimbursement for interpreter services, and refining risk adjustment models to account for social determinants of health are critical to improving equity in cancer care for LHS+ populations.

Discussion

This manuscript highlights the substantial obstacles and disparities LHS+ face as they navigate the health care system, particularly within surgical oncology. The Hispanic Paradox, while suggesting favorable outcomes, can obscure the reality of worse outcomes for LHS+ patients in certain contexts, as shown through stratified research. This paradox is maintained by a complex interplay of factors such as selective migration, the healthy migrant effect, survival bias, cultural protective factors, and healthier lifestyles.

Among the most critical findings is that, despite the paradox, disparities in surgical outcomes are evident, particularly in postoperative complications, delayed treatments, and emergent surgeries for LHS+ patients. Contributing factors include LEP, lower socioeconomic status, cultural barriers, and limited access to timely medical care. These disparities are especially pronounced in cases of breast cancer and HCC.

Our review highlights the importance of stratified studies that focus on specific LHS+ subgroups (e.g., Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban) to better understand the unique challenges each group faces. Future research should focus on stratified studies examining specific LHS+ subgroups to better identify targeted interventions. Critical gaps include understanding the role of genetic predispositions, environmental exposures, and health care policies in treatment accessibility. Additionally, more research is needed to evaluate cultural influences on treatment adherence and the long-term impact of delayed interventions on cancer survival. To generate rigorous evidence that can directly inform practice and policy, future studies should include prospective multicenter cohort studies or cluster randomized trials evaluating interpreter and navigator interventions for LHS+ patients.

Beyond structural and cultural barriers, limitations inherent in the existing literature must also be considered. Retrospective study designs dominate the field, with many analyses restricted to single institutions or underpowered by small cohorts. These limitations may conceal the true magnitude of disparities across LHS+ subgroups. Also, the possibility of publication bias exists, as studies finding significant disparities may be more likely to publish than those finding no difference.

In conclusion, addressing these disparities will require sustained efforts to improve health care equity, particularly in surgical oncology, where timely access to care and culturally sensitive approaches are essential for achieving better outcomes for LHS+ patients.

.png)

.png)