INTRODUCTION

Latino individuals are 1.5 times more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) than non-Hispanic white.1–4 In 2025, it is estimated that 13% of Latino adults older than 65 years old have ADRD, which represents approximately 600,000 individuals in the U.S, and it is projected that by 2060 this number will increase by 832%, reaching 3.5 million. Despite higher prevalence, there is evidence of health disparities in multiple aspects for Latino individuals, such as higher rates of under-diagnosis,5–7 and lower utilization of medications,8 behavioral treatments, and community services related to ADRD.9,10 These health disparities have been exacerbated by a lack of health care professionals trained to provide culturally relevant care.

In the U.S. there is a large deficit in the workforce trained to treat dementia,11–16 with only 8,220 geriatricians serving 52.4 million individuals over 65 years old, resulting in millions with limited access to a specialized diagnosis and management of cognitive symptoms. This has resulted in an increased burden to primary care providers (PCPs), with 82% of them being on the frontline of dementia care,17 but 40% reporting being uncomfortable making a diagnosis.18 However, nearly half of PCPs sometimes choose not to assess a patient for cognitive impairment due to a lack of confidence in making a diagnosis and uncertainty around available resources,19 resulting in approximately 40% of older adults with probable dementia being undiagnosed.5,20

Despite PCPs’ pivotal role in the early detection and management of ADRD, there is evidence that various organizational and policy factors influence their ability to deliver culturally competent and equitable care. Understanding the extent of these factors and how they manifest in daily practice is a necessary step to identify solutions to the health care disparities experienced by Latino older adults with ADRD and their families. This study aims to explore PCP perspectives on the organizational and policy barriers they face, which in turn can be used to inform the development of models that enhance early diagnosis of ADRD in primary care settings that are feasible to implement, sustainable, and have buy-in from clinicians and administrators alike.

METHODS

Participant Recruitment and Data Collection

This study is a secondary analysis of a qualitative study described in detail elsewhere.21 In brief, the study recruited PCPs using snowball sampling techniques and conducted interviews about ADRD care in the Latino community. The inclusion criteria were being a physician (MD or DO), nurse practitioner, or physician assistant who currently or recently provided primary care services to Latino families with ADRD in the U.S.

Theoretical Framework

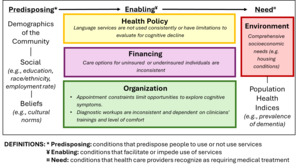

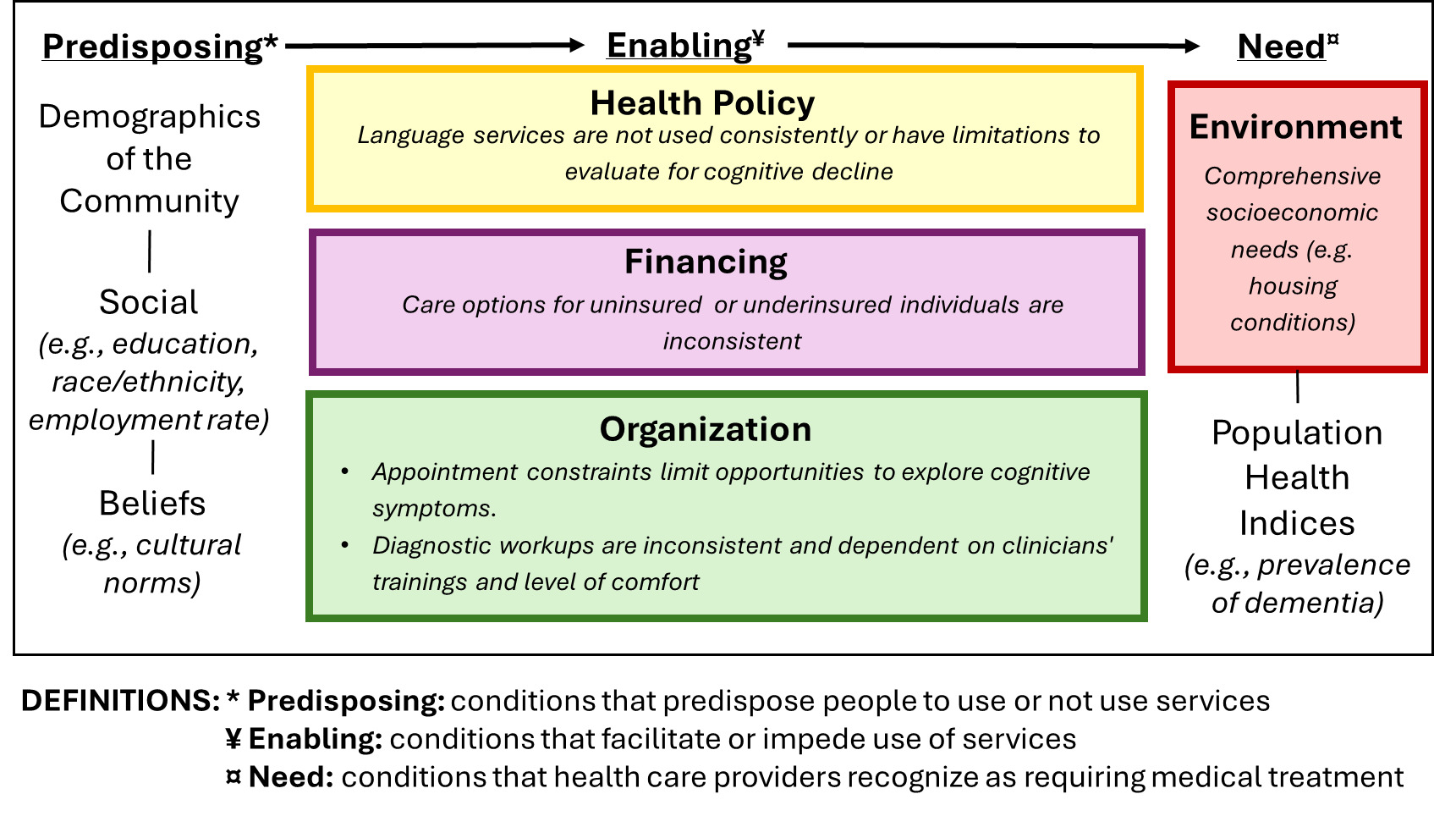

Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use22,23 establishes that health outcomes result from contextual and individual factors that interact at the community, organization, and individual levels. Individual characteristics include genetic factors, social support structures, economic factors, and beliefs. For the purpose of this study, we are exploring only the contextual characteristics, which refer to the circumstances and environment of health care access and include community- or societal-level characteristics and health care organization characteristics. Contextual organizational factors refer to the amount, distribution, and processes for delivering services in a community, including outreach programs and office locations. Although Andersen’s model has been widely used to explain access to care, definitions for its domains vary across studies.24

Data Analysis

Two reviewers independently conducted deductive qualitative content analysis. The Rigorous and Accelerated Data Reduction (RADaR) technique was employed to organize and code data in Excel.25 A research assistant performed initial open coding of the first five transcripts and reviewed them by the first author to ensure accuracy. The themes were identified and refined through iterative coding and discussions. Consistency was maintained by dual coding every fifth transcript. No measures of interobserver reliability were applied. A qualitative methodologist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison reviewed the final themes and codes.

Ethics/Institutional Review Board Review

The University of Kansas Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved the project (STUDY00145615). Participants provided informed written consent online. A Data User Agreement facilitated the sharing of de-identified data between institutions. The UW-Madison Health Sciences Institutional Review Board determined that the research met exemption criteria.

RESULTS

The analysis of qualitative interviews with 23 PCPs revealed five key themes at the contextual level. Figure 1 shows the identified themes organized across three categories in Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use.22,23

Health Policy and Financing

PCPs reflected that mandated language services, while intended to improve care, often faced access and quality issues, hindering accurate diagnosis and effective communication with patients. PCPs also identified significant challenges related to insurance eligibility and care options for uninsured individuals, which required further assessment by some team members. These constraints limit the ability of PCPs to provide comprehensive and culturally competent care (Table 1).

Organizational Factors

The availability of staffing and resources dictates the type of care that can be offered, leading to inconsistent protocols and options across different practices. Many PCPs reported that their usual process includes ruling out reversible causes of cognitive decline such as anxiety, depression, medication interactions, and sleep apnea, followed by the use of cognitive screening tests such as the MOCA or SLUMS to decide if a referral to other services is needed. Meanwhile, other physicians commented that their ability to conduct thorough workups is influenced by their level of training, time availability, and comfort with ADRD care. Appointment constraints were a common theme across multiple providers, highlighting how expectations for 15- to 20-minute appointments limit their ability to investigate cognitive complaints in the presence of other complex conditions (Table 2).

Need – Environmental Factors

While PCPs recognized the importance of comprehensive assessments that included evaluations of patients’ home and social environments, these were often constrained by a lack of follow-up resources. This limitation hindered the ability to fully understand the multifaceted needs of Latino patients with ADRD, including their need for housing, assistance for activities of daily living, and safety. This limited their capacity to provide resources for individuals (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

This study highlights the significant impact of organizational and policy factors on the provision of ADRD care for the Latino community. This is one of the few studies in the Latino community that focuses on exploring the role of organizational and policy factors in accessing health care, as most studies take a rather individual approach.26–28 The findings reveal key themes related to policy constraints, resource-dependent care, comprehensive assessments, and family involvement, which collectively shape the ability of PCPs to deliver culturally competent and equitable care.

The study found that insurance eligibility poses substantial barriers to effective ADRD care. Previous research shows that PCPs treating Medicaid-insured and uninsured patients face resource constraints, limiting access to specialized diagnostics or multidisciplinary care coordination due to administrative barriers.29 Medicare coverage enables basic diagnostic imaging and specialist referrals, but PCPs report challenges in navigating prior authorization requirements and coverage limitations for newer therapies or biomarker testing, which delays diagnosis and complicates treatment plans.29,30 For uninsured or underinsured patients, PCPs often prioritize cost-sensitive approaches, such as deferring advanced neuroimaging or relying on nonpharmacological interventions.31

Furthermore, regarding language services, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Executive Order 13166 require health care organizations that receive federal funds, such as through Medicare or Medicaid/CHIP, to provide interpreter services for Limited English Proficiency (LEP) individuals. Despite this legal requirement, it is known that not all hospitals comply; in 2010, 13% of hospitals fully complied with all National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS).32 Our study also reflects that for cognitively impaired patients, the risk of miscommunications due to inconsistent use of interpreters might increase the risk of errors in medication instructions or diagnostic clarity, which can directly harm individuals with diminished capacity to self-advocate or correct misunderstandings.33

The availability of staffing and resources dictated the care offered, leading to inconsistent protocols and options, which is consistent with studies that highlight the challenges faced by caregivers in resource-limited settings.34,35 Structured interventions that support family caregivers and enhance their engagement can significantly improve the quality of ADRD care, but accessing this is also limited by financing options. Insurance type also affects care continuity: fee-for-service Medicare patients with dementia experience higher hospitalization rates compared to those in managed care plans, underscoring the role of insurance structures in care stability.36 PCPs recognized the importance of comprehensive assessments, including evaluations of patients’ home and social environments, and there is an expectation that the emerging diagnostic biomarkers can enhance the evaluation and management of ADRD in primary care settings.37 However, appointment constraints and lack of follow-up resources limit their ability to conduct thorough assessments, which on many occasions they have not received training on. Integrating ADRD-specific content into the curricula of medical, nursing, and allied health programs would help address the current workforce gap and enhance providers’ confidence and competence in delivering culturally responsive care. Furthermore, there is growing evidence on the need to develop more comprehensive educational resources for both current and future health care providers that go beyond lecture-based learning and include interactive training modules, culturally tailored case studies, and simulation-based learnings.38–43 This educational emphasis aligns with broader population health goals by equipping providers to better serve diverse aging populations and reduce disparities in dementia diagnosis and management.

Limitations of the study

This study has several limitations, including the sample size and geographic scope, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. Although the study participants were recruited from various regions across the United States, the geographic distribution may not fully capture regional differences in health care delivery and policy environments. Furthermore, health care policies and organizational practices are dynamic and can change over time. Additionally, our study does not include the views of other stakeholders, such as patients, family members, or policymakers, and using snowball sampling techniques, while effective for recruiting participants, may introduce selection bias, as PCPs who chose to participate might have specific characteristics or experiences that differ from those who did not.

Implications for future research and public health impact

The current study has implications for future research. We have identified five themes across three categories in Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use. Future studies should assess the prevalence of these themes and their impact on the health of Latino families with ADRD. While cross-sectional studies are ideal to assess prevalence, longitudinal studies that track changes in PCP practices and policy impacts over time would provide a more comprehensive view of the evolving landscape of ADRD care in this community. PCPs highlighted the need for resources for Latino families with ADRD. While culturally tailored evidence-based interventions exist,44 these might not be ready to implement in the real world. Future studies should explore how to best implement these evidence-based interventions in primary care.

Our study also has implications for public health. Issues with language services highlight the importance of integrating these services in a way that they do not impact the workflow. In-person and videocall options are preferred to phone call options. Our findings also suggest that it will be important to standardize assessments so that all, and not just those with optimal health care coverage, have access to the gold standard. Minimum standards for ADRD care also need to be developed and disseminated to ensure that all primary care clinics, irrespective of their budgets, have the capacity to provide appropriate ADRD care to Latino families. These standards might have to include available remote options and workups that low-resource clinics can conduct or easily refer to. The National Institutes of Health and the Alzheimer’s Association have free materials for Latino families, some of which have shown to reduce depressive symptoms among caregivers.44,45 All clinics could, in theory, request these to hand out to their Latino patients and their families.

Conclusion

Addressing organizational and policy barriers is essential for improving ADRD care for the Latino community. Targeted interventions that enhance PCP training, develop accessible service models, and promote family involvement can significantly improve early diagnosis, preventive care, and quality of life for individuals with ADRD. Further studies are needed to explore the cost-effectiveness of new policies and protocols that address the identified barriers and improve care delivery.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Perales-Puchalt thanks the national and local organizations that have partnered with him to conduct present and past research since 2015. The research team thanks research participants included in all stages of this research as well as anyone who has contributed directly and indirectly to this research. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors alone, and endorsement by the authors’ institutions or the funding agency is not intended and should not be inferred.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities under Award Number K01 MD014177 (PI: Perales-Puchalt), the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers P30 AG072973, R01 AG082306, and K99 AG076966 (PI: Mora Pinzon), the National Institute of General Medical Sciences under Award Number P20 GM139733, and the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant UL1TR002373. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflict of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent Statements

The University of Kansas Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved this project (STUDY00145615) on 4/20/2020. A Data User Agreement between the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the University of Kansas Medical Center was executed to allow the sharing of de-identified data for this analysis. The UW-Madison Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (IRB) determined that this research met the criteria for exemption.

Data availability statement

Data is available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author at jperales@kumc.edu.

Disclosure of Use of AI

During the preparation of this work, the author(s) used Grammarly and Microsoft Copilot to improve the manuscript’s readability and format. After using these tools, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the publication’s content.